When Chris was accepted into the Georgetown’s School of

Foreign Service, he didn’t think of himself as a first-generation

college student. Acknowledging his first-generation identity and how it

influenced his path came years later, but the label assigned by his

college is only a part of Chris’s individual story.

His

parents, both Vietnamese refugees who had not gone to college, raised

him in south Florida. Chris, who did not want to use his last name, knew

he’d earned a golden admission ticket, but he didn’t know that getting

in was only half the struggle. He hadn’t considered how his parents’

lack of higher education might influence his own college studies. “I did

homework with my classmates for the first time and I found myself

getting defensive about what little knowledge of college I had coming

in,” Chris said, describing the anxiety and distress he experienced

studying, taking tests, and meeting classmates. “I was playing pretend

the moment I had my first meaningful conversation with someone, and I

consequently felt lost the next year and a half.”

More schools are focusing on supporting students like Chris. But in

their goal to increase access to higher education, schools label young

people in ways that isolate rather than include

them particularly where colleges and the support systems they develop

for these students automatically equate being first generation with

being low income, as many studies suggest.

As a sociologist,

Celine-Marie Pascale, a professor and the associate dean for

undergraduate studies at American University, where I also teach, is

concerned with the language and attitudes that develop around culture,

knowledge, and power. When Pascale was a first-generation graduate

student, 17 years after earning her undergraduate degree, she was

awarded a scholarship and asked to visit donors. “I was incredibly

grateful, of course; I could not have gone to school without it. But I

became weary of going to events and representing the poor student they

were saving. It felt demeaning,” she said.

The

labels aren’t always intentional, and they aren’t always bad. Colleges

anticipate and define student categories—like low-income,

first-generation, and minority mostly based on voluntary Common Application

data provided before a student ever arrives on campus. While students

aren’t required to disclose their parents’ educational backgrounds—and

many don’t self-identified first-generation students are often linked to

or assumed to have economic disadvantage. Students may also choose not

to disclose their first-generation status; professors and classmates

won’t know unless they claim the label. But labels that assume

first-generation always correlates with low-income may get in the way of

the more important conversation of how individuals relate to their

college community and larger culture and foster feelings of resentment.

Does

it matter if first-generation students are also low-income? What about a

first-generation student of color who comes from a family of means? How

many labels are necessary to understand first-generation students’

needs? Labeling theory has been well established in multiple

disciplines, and when applied to the classroom, teacher expectations may

influence student performance. If a teacher lowers standards because he

assumes a student needs the accommodation, the student’s true potential

won’t be measured. A label may unintentionally shape a teacher’s

reaction, meaning she may assume a certain behavior results from the

label rather than the individual. At a critical juncture in a college

student’s cognitive development, the combination of labels may hinder

more than help.

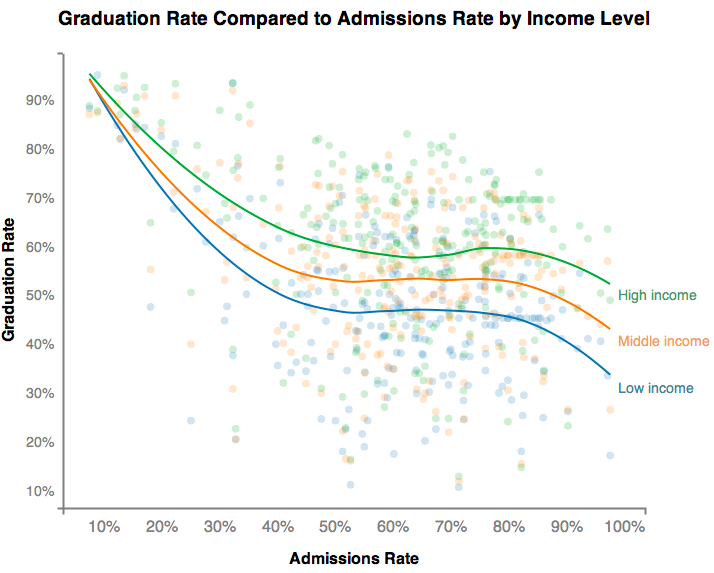

Attending college is among the best ways to move up the economic ladder. Bachelor’s degree holders earn more than two million dollars more over a lifetime than those without. Given the rising costs of education, many fear that good higher education is getting out of reach of the poor.

And when poor students do attend schools, they too often choose the schools for which students have the worst outcomes: Low graduation rates, high debt and low future earnings.

To battle these forces, the federal government implemented the College Scorecard

initiative. This initiative is an attempt to highlight those schools

which are low cost and financially remunerative, and to condemn those

that are neither. While the primary feature of College Scorecard is a

website at which students and parents can look up statistics about

schools, another aspect of the initiative was the release of a huge,

publicly available dataset, which includes a breakdown of outcomes by

economic background.

We decided

to use this data to see which schools are helping lower income students

get into the middle class, and which are not. Where exactly does a low

income student get the “biggest bang for their buck?” The answer seems

to be that, if possible, poor students should attend the elite

institutions that lead to high salaries and have generous financial aid

programs. If these highly selective institutions are out of reach, as

they are to most Americans, a technology-focused state school may be the

best option.